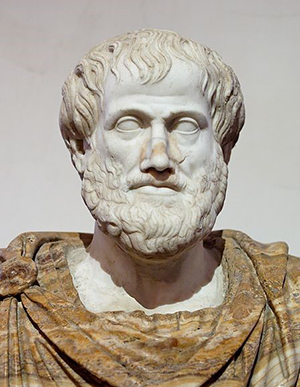

In his work, On Rhetoric, Aristotle offers instruction on the art of persuasion. He identifies three modes or “offices” of persuasion. In Greek they are ethos, logos, and pathos. In order to cast a persuasive argument, Aristotle posits that we must construct from all three elements.

In order to be accepted by the intended audience, the argument must come from credible sources. This is the ethos of the argument. No matter how appealing an argument may be otherwise if the sources of its logic and foundations are not themselves credible, it is liable to rejection. Aristotle advises that we must make our case for our own credibility and that of our sources.

The credible argument must also make sense. Its internal logic and supporting evidence must follow point to point across a line of reasoning that is as unbroken as it can possibly be. While our every argument can’t be ironclad and undisputable, they must be sound in order to be persuasive. Big leaps of logic and gaping unexplained holes in our reasoning cast well-deserved doubt on our conclusions. This is Aristotle’s logos or logic.

Even a logical argument from a reasonably credible source needs the third office, pathos, if it is to elicit action by its target audience. In Aristotle’s view this is the emotional connection that drives us from a polite nod of the head to real effort or change. We have to connect with the emotional drivers of the audience in order to move them to a response. If we want meaningful action, it is simply not enough to present our argument logically and credibly. We must invoke Aristotle’s third office.

By now you are probably wondering what in the wide, wide world of sports all this philosophizing has to do with systems engineering. As practitioners of this discipline, we are regularly placed in the position of advocating (or justifying) the means and methods by which we operate. Whether that means selling our services to an unknowledgeable customer or supporting rigorous design discipline to fellow professionals accustomed to short-circuiting or avoiding crucial steps, we must make the case for systems engineering over and over in our practice.

In making that case, it helps to be aware of and pay due homage to Aristotle’s levers for argument. Each of them apply and, in fact, we probably make intuitive use of one or more of them now. But by understanding and applying all three of them, we can become even more effective advocates for the many advantages of our discipline.

We can begin to establish ethos through the use of our direct experience. We all know of personal examples of the value of systems engineering applied in particular settings. Citing these experiences lends credibility to our arguments. When we couple these with support from the abundance of research available to us in the information age, we build powerful credibility from which to make our points. By joining INCOSE and mining the rich trove of articles, webinars and research work deposited there by our colleagues, we can make ourselves better practitioners and stronger advocates. Participating in Chapter and International activities and working groups yields even greater knowledge and experience to build the ethos for our case.

Having established credibility, we then need to move to making a logical and well-supported argument. If we want action, we need to establish a path that requires and enables it. Our reasoning should be solid with each step following the last and providing a base for the next. Our logical progression should make sense and be understandable to our audience. A solid path from the as is to the to be is paved with the logos of our case.

Finally, we must ground our argument in the needs of our audience. Where we want action- like accepting our help in designing their system solutions or adopting our discipline and methods in their engineering practice- we must connect our request for it to their needs and pains. By doing that, we show that we connect with their problems and, even more importantly, we can truly help them.

The case we make to the world- customers and colleagues alike- should be grounded in Aristotle’s timeless wisdom around the three offices of rhetoric. We may not call it rhetoric (a term that has been saddled with pejorative baggage since his usage) or think of ethos, logos, and pathos but we should be credible, logical, and helpful as we advance our discipline in the world. And it wouldn’t hurt to murmur a word of thanks in honor of our long gone mentor as we do it. Thanks for the reminder Ari.