Earlier this year, I did a webinar entitled “Getting Started on Enterprise Architectures.” In that webinar, I introduced the concept of operational architectures. The topic of operational architectures has come up in conversation lately and I thought this article would be a good time to explore the concept of operational architectures a bit further.

Before we delve into operational architectures, let’s review the concept of a system architecture. The term “architecture” refers to the art and science of designing and constructing something. The title of “architect” without any other qualifier in the title usually refers to someone who is skilled in designing and constructing buildings. As a building architect, one must take into consideration the many subsystems that are necessary for the end product. The architect must consider electrical, plumbing, heating and ventilation, foundation, structure, roofing, and landscape, to name a few.

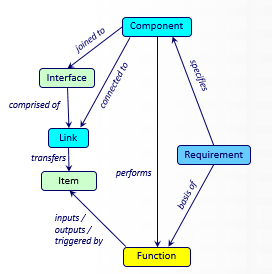

Accordingly, when we use the term “system architect,” we are referring to someone who is skilled at designing and constructing systems. Like the building architect, the system architect has to account for and integrate requirements, physical entities, functions, and connections between components. To communicate our design, we develop diagrams such as hierarchy, structure block definition diagram (bdd), classification bdd, interface, physical block, activity, etc. And, we understand how the classes and entities relate to one another in terms of a System Architecture schema.

Figure 1. System Architecture Schema

Generally, we designed the system based on a set of stakeholder inputs. Sometimes these are expressed in terms of a specification given to us that represents what the acquiring agency desires from the system.

In some instances, the top-level system design requirements are defined as the result of a detailed analysis of the capabilities and operational activities that the system needs to support. The capabilities and operational activities that a system must support come from an analysis using an Operational Architecture. Operational architectures express the missions, goals, operations, and organization of a business unit. The operational architecture express the what, when, and where that a business unit needs to accomplish without regard to how it is implemented.

As an interesting aside, notice here that operational architectures deal with “business units.” If you are reading this article and support a military branch, a “business unit” sounds awkward. I specifically used this language because the concept of operational architectures was thought of and developed in commercial industry. The military adapted these ideas in the 1990s to develop what we know in the military domain as the DoD Architecture Framework (DoDAF).

When we think of managing a business unit, we need to look at the goals, objectives, capabilities, operation activities, and organizational structure that the business needs to possess in order to fulfill its purpose and stay in business. As we perform this analysis, we do so without regard to how it is implemented, and without regard to a preconceived set of systems. So it follows that the operational architectures would have a different set of classes to express the architecture. The classes for an operational architecture are presented in the following table.

| Class | Definition |

| Operational Node (or Performer) | An organization in the business that produces, consumes, or processes information or material. |

| Mission | Identifies a task, together with its purposes, that clearly indicates the action to be taken and the reason therefore. |

| Capability | The qualities, abilities, features, etc. that can be used or developed to achieve goals. |

| Operational Task | An action to be performed in support of a mission. |

| Operational Activity | An action or process needed to fulfill a mission, task, or role. Transforms one or more inputs into outputs. |

| Operational Item | The data or physical things that are needed to flow between operation activities, and thereby, Operational Nodes. |

| Needline | Identifies the requirement to exchange data or physical things between two Operational Nodes (or Performers). |

Table 1. Class Used in an Operational Architecture

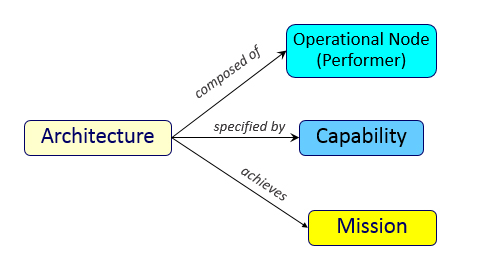

When we start developing an operational architecture, we begin by identifying the top level characteristics of the business in terms of Operational Nodes (sometimes called Performers)—the mission areas supported and the capabilities needed to operate the business. We can relate these areas to begin developing a schema for the operational architecture.

Figure 2. Key Classes in an Operational Architecture

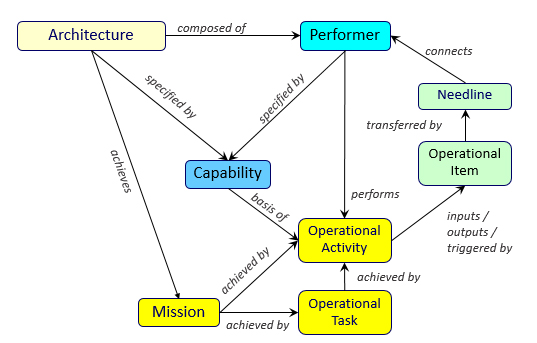

As we expand our thinking about the operation of the business, we understand that there are relations between the top level classes defining the operational architecture. Thus, the operational architecture schema expands to provide the following structure:

Figure 3. The complete set of classes for an Operational Architecture

The classes and key relations provided in this schema allow us to express what the business unit must be able to accomplish given a set of mission definitions, a particular structure of performers, and a set of identified capabilities. The Operational Architect is able to construct the sequencing of operational activities that must be performed using the given performers.

All of this information is abstract in nature, and the implementation of how the business is going to meet the structure defined is not accomplished in this analysis. Because this structure is abstract and there are no definitive systems identified, system engineers generally have a difficult time constructing and understanding the operational architecture.

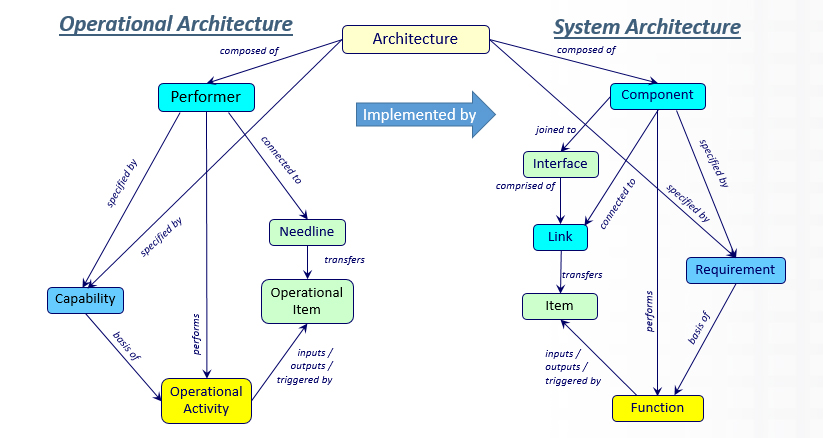

But eventually we need to relate this abstract information to identify and develop systems to implement the operational architecture. If you look closely at the operational architecture schema provided in Figure 3, you can see that it is constructed almost as a mirror image of the system architecture schema provided in Figure 1. When we align these to architectures, you can see how the operational schema can be implemented by the system schema, as shown in the following diagram.

Figure 4. Integrating Operational and System Architecture

The end result is that the operational architecture, what the business must do, can be expressed in terms of the operational architecture. Implementing the operational architecture by development and alignment with definitive processes and systems moves the design from what the business must do to how the business will accomplish the operational architecture.

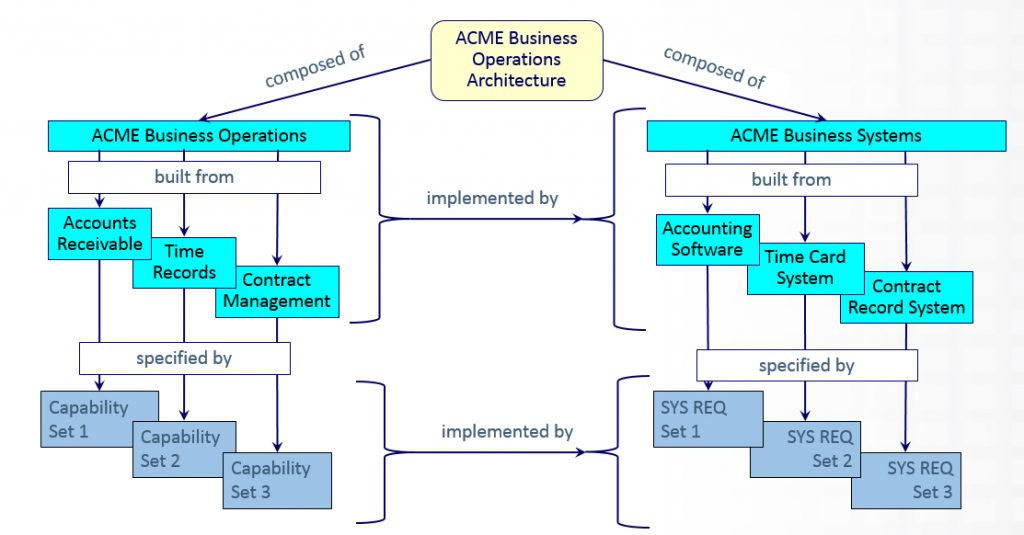

Let’s look at a condensed example of how the operational and system architectures relate to one another. In the diagram below, we have the “ACME Business Operations Architecture.” The ACME Business Operations unit has three operational nodes: Accounts Receivable, Time Records, and Contract Management. Each of these operational nodes has a set of “specified by” Capabilities.

The Business Operation unit is “implemented by” the ACME Business Systems Architecture, which is “built from” three separate systems: Accounting Software, Time Card System, and Contract Record System. Each operational node fulfills its role with the unique systems. And in turn, each of the individual systems supports a unique operational node with the overall business operations center.

Each operational node within the overall business operations area has a set of capabilities that must be achieved. The capabilities desired in each business area are “implemented by” a set of system-level requirements that specify what the particular system is capable of doing.

Figure 5. ACME Business Operations Architecture Example

Constructing both an operational and a system architecture gives us a business-wide view, and this is called an enterprise architecture. Using this, we can evaluate how changes in the business operation are affected by the systems and processes. Likewise, we can evaluate how a change in a system, for example, a replacement or a modification, will affect business operations.

Eventually, we may want to expand or change the strategic purpose for our business. Using the operational architecture, we can examine how we would want to make changes across the enterprise to support the new business opportunities. And, from there, we can determine what changes need to be made in the system architecture that support the business structure.

In this article, I introduced the concept of an operational architecture, explained how the operational architecture is constructed, and how the operational architecture is related to system architecture and the systems we generally focus on as systems engineers. Finally, I examined a condensed example of an operational and system architecture and how they are related to one another, and looked at how they can be used to examine changes in either business operations or system improvement or replacement.