Here is a 4 minute video that conveys the main points of this blog post.

As the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) looms large on the public radar screen, it consumes a greater and greater share of our attention. We tend to get swept up in the drama and emotion unfolding like a science fiction thriller and forget that we have tools and skills that can be leveraged against the effects of the pandemic.

This is true even of the anxiety that is being created as our daily lives are upended and changed for an indeterminate period of time. The response to the pandemic itself is being handled at the government and enterprise levels. This essay addresses how we design and handle our personal coping strategies. It is not addressed to the greater societal and medical issues around the epidemic itself—although those problems are certainly amenable to solutions using systems thinking and systems engineering approaches. The concern set out above is that we are swept up in the drama and emotion of the pandemic, and that causes us to lose sight of the practical steps that we can take to manage our coping behaviors. Therefore, we will discuss how we can manage our own emotional responses and not how we can eliminate or mitigate the pandemic itself.

The lessons of systems engineering can be applied to the development of strategies that we use to cope with the new limitations and conditions that we are facing. Even though the pandemic and its emotional wake do not immediately appear similar to problems that most systems engineers encounter in the regular course of their duties, the problems it is creating for our psyche are amenable to solutions using principles that systems engineers apply every day.

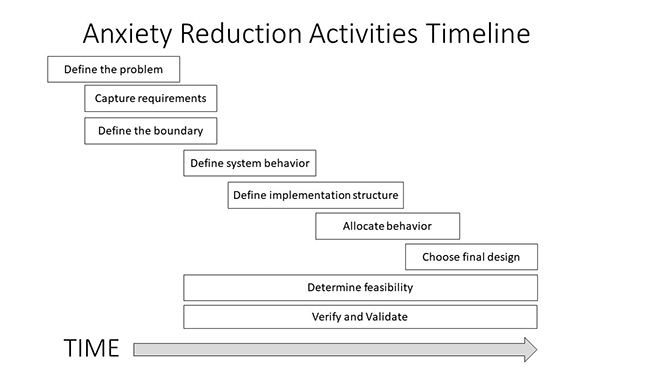

With all due apologies to the original authors and subsequent elaborators of a familiar representation, the following diagram (Fig. 1) provides a systems engineering flow for working our COVID-19 anxiety problem.

Fig. 1

STEP 1: Define the problem

This step in the flow should always be the point of beginning for systems engineers. Without an accurate understanding of the problem to be solved, the solution will always be misdirected to the extent of the misunderstanding. Russell Ackoff famously said, “Successful problem solving requires finding the right solution to the right problem. We fail more often because we solve the wrong problem than because we get the wrong solution to the right problem.”

The anxiety that we are seeking to reduce in our response arises from our efforts to navigate a new and uncertain path. Dr. Bethany Teachman, a University of Virginia professor of psychology and the leader of UVa’s Program for Anxiety, Cognition and Treatment Lab, pointed out in a recent article for UVAToday, “Key ingredients that contribute to anxiety are a sense of uncontrollability and unpredictability, and the current situation is high on those characteristics because we’re still learning a lot about how it spreads and its impact in different communities. As a result, the uncertainty we feel fuels anxiety because we wonder if we’ll be able to respond effectively to the threat.” Dr. Teachman went on to explain that our fear makes it “harder to distinguish between reasonable prevention measures and panic-driven measures that follow from intolerance of uncertainty.”

What we are seeking from this solution are ways to cope with the anxiety of uncertainty that allow us to sort the “reasonable (COVID-19) prevention measures” from the “panic-driven measures” that anxiety produces in us. That is our problem in a nutshell.

Step 2: Capture the originating requirements

The solution we seek must, first and foremost, give us ways of managing our anxiety. These ways must be practical and doable. We would also like any strategies to be grounded in research and/or experience, thereby offering us some assurance that they will work. These are the high-level requirements for our solution.

Step 3: Define the system boundary

This is also a critical step. Designing a solution that crosses the boundary into a space that we do not control will actually make the problem of our emotional response worse. The line between what we can control and what we cannot is our solution boundary. As we craft a set of strategies, we are seeking actions that we can actually take to reduce our own anxiety.

While this is to some extent obvious, it has long been a problem for humans in and of itself. Enough so that psychologists and philosophers have found it necessary, for as long as there have been psychologists and philosophers, to tackle the concept. Epictetus, a first century Greek Stoic, is reported by his student Arian as having taught, “Happiness and freedom begin with a clear understanding of one principle: Some things are within our control, and some things are not. It is only after you have faced up to this fundamental rule and learned to distinguish between what you can and can’t control that inner tranquility and outer effectiveness become possible.”

Happiness and freedom being the antithesis of anxiety, they are not only our boundary, but also hallmarks of the solution itself. By recognizing that our boundary is the line between what we can and cannot control, we are one step closer to reducing our anxiety and increasing our happiness.

Step 4: Define the system behavior

The behavior our system must exhibit consists of gathering information (about the pandemic as well as about precautions and strategies for implementing them). It may also include provisions for working at home (if that constraint is applicable to your situation), for shopping for necessities (food, household items, medicine etc.), for communicating with friends and family, and for health and wellness strategies that you may adopt.

Strategies aimed directly at stress/anxiety reduction should certainly be a part of the behavior of any systemic solution for anxiety reduction. Ranging from the “time-boxing” of worry suggested in Dr. Teachman’s article to the time-honored mindfulness and meditation techniques growing out of religious traditions (Buddhist and Christian, for example) and widely practiced today in and out of the religious communities, strategies for directly attacking stress and anxiety abound. Specific practices can be selected from a wealth of online resources for inclusion in a specific solution. (Here are some examples.)

Step 5: Define the implementation structure

A key building block in the definition of the implementation structure is to have it fed by quality information. The first kind of information required should provide an up-to-date understanding of the status of the pandemic itself and the recommended precautions in dealing with it. Turning again to Dr. Teachman, she advises, “I encourage people to choose a select number of trusted news sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Virginia Department of Health [substitute your state department of health], and check those sources at set times—for example, twice a day—and then focus on other activities.” Notice the revision to the system behavior suggested by Dr. Teachman (“check those sources at set times”). This “time-boxing” is an important part of limiting the anxiety-driven reflexive checking of the news and the resulting increase in anxiety.

A second kind of information will include practical advice about working in this environment. Many productivity websites have dedicated posts, pages or resource lists to the newly exploding work-from-home environment. Like the suggested limitation on access to pandemic news, the focus on the mechanisms of remote work provides a decrease in uncertainty and an increased attention to “doable” solutions to the practical problems at hand.

The solution must make provisions for the infrastructure for work—a space conducive to working, internet connectivity and bandwidth, and the tools for accomplishing work tasks. This may consist of health precautions in your usual workspace or involve the creation of a new work-at-home environment.

The shopping interactions required for necessities must be provided within the constraints of limiting interpersonal contact. Meals can be ordered for pickup or delivery from local restaurants. Groceries can likewise be acquired through online orders for pickup or delivery from local stores or as a service by meals-in-a-box providers. Many local pharmacies have drive thru service windows for medicine supplies. All of these mechanisms and more must be identified to effectuate the behaviors required of the solution.

Step 6: Feasibility, verification and validation

Throughout this process, we should be testing the feasibility and effectiveness of the solution we are crafting. We may be attracted to the benefits of a meditation practice only to discover that the one hour of focused mindfulness recommended in a particular resource is not practical for us as beginners. We should not be afraid to reexamine that aspect of the solution and substitute a 3-5 minute guided meditation as a gateway to mindfulness as a technique.

The same can be said for vendors, products and other decisions around aspects of our solution. The good news is that the process of verifying and validating them can be as good for us as the ultimate solution itself. It represents time away from the uncertainty of obsessing on things beyond our control and puts our focus on decisions and actions within our ability to affect.

Conclusion

The selection, use, and tweaking of these strategies provide a much needed alternative to obsessing over the latest rumor or development in the pandemic which is beyond our individual control. This reduces anxiety and helps to meet the need that drives the solution design. By limiting our focus on the uncontrollable uncertainty of the overall pandemic environment and concentrating our attention on what we can reasonably do to structure our response, we can trade a large measure of uncertainty for achievable goals and strategies. This will go a long way to relieving our anxiety and helping us to navigate an unsettling time in our history.